On Tuesday, the world lost pioneering science fiction author Ray Bradbury at age 91, and since then everybody and their mother has (quite correctly, in my view) been making all sorts of bereaved noises about his passing being a tremendous loss not just to our ghettoized little genre of science fiction but to literature and the world of letters in general.

They’re absolutely right.

That said, it’s become de rigeur upon the passing of an author with a career as long and storied as Bradbury’s to throw about words like “legendary” and “seminal”, and while authors don’t usually have long and storied careers without something of such traits, the overuse of those terms threatens to diminish the significance of those who truly were legendary and seminal. Like, for instance, Ray Bradbury.

So let’s take a look at why he really was all that…

Of course, his was one of the big names of science fiction, thanks to novels that crossed over into mainstream literary success (Fahrenheit 451 and The Martian Chronicles, most notably) and successful media adaptations of his work (like Something Wicked This Way Comes, along with the aforementioned pair of novels).

But Bradbury didn’t set out to be a mainstream, big film guy. In the beginning, he was a fan. As a teenager in the 1930s, before his writing career had really begun, he was rubbing elbows with the likes of Robert A. Heinlein, Henry Kuttner, Leigh Brackett and Forrest J. Ackerman at early sci-fi conventions. He was honing his craft in fanzines like Imagination! and his own Futuria Fantasia.

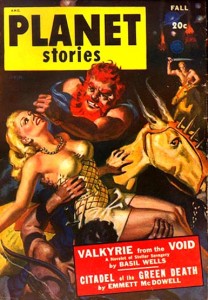

Once his professional writing career got off the ground in the early 1940s, it didn’t take him very long to change the state of the genre. By the late ’40s, stories like “Mars Is Heaven!” (Planet Stories, Fall 1948), “Dark They Were, and Golden-Eyed” (Thrilling Wonder Stories, Aug 1949) and “A Sound of Thunder” (Collier’s, 28 June 1952) were catching people’s attention.

And with good reason. These stories were full of literary merit by any measure—they could be moody and atmospheric, and use their otherworldly imagery to comment insightfully upon truths of the human condition like prejudice and short-sighted ignorance of history; but, unlike those of the dour “New Wave” authors of the ’60s and ’70s who were determined to prove their sociological bona fides at the expense of all wonder and fun, Bradbury’s stories were still joyfully, gloriously science fiction. Bradbury’s use of other planets, travel through time and space, and telepathic virtual reality was unapologetic. He wasn’t slumming it in the pulps until he made it as a “real” author, he was where he belonged in the pulps, and while he insisted on defining his work as fantasy rather than science fiction, it was still, ultimately, written by a genre fan for genre fans.

In that combination of good writing with unabashed, genuine imagination, Bradbury was a pioneer. Those of us who grew up after the New Wave revolution of the ’60s are used to science fiction being taken seriously as a literary genre (in theory, at least), but I believe that none of those who blazed sci-fi’s trail into respectability—Le Guin, Ellison, Aldiss, Delany, et al—could have done so without Bradbury going there, to a certain extent, first.

That my friends, is what we truly mean by “legendary” and “seminal”, and that was Ray Bradbury. May his work not just always be remembered, but may it continue to be consumed with the respect and, yes, enjoyment that it still warrants to this day.